LOVE LETTER: ELEANOR ROOSEVELT AND LORENA HICKOK

- LGBTQ Pride

-

Apr 05

- Share post

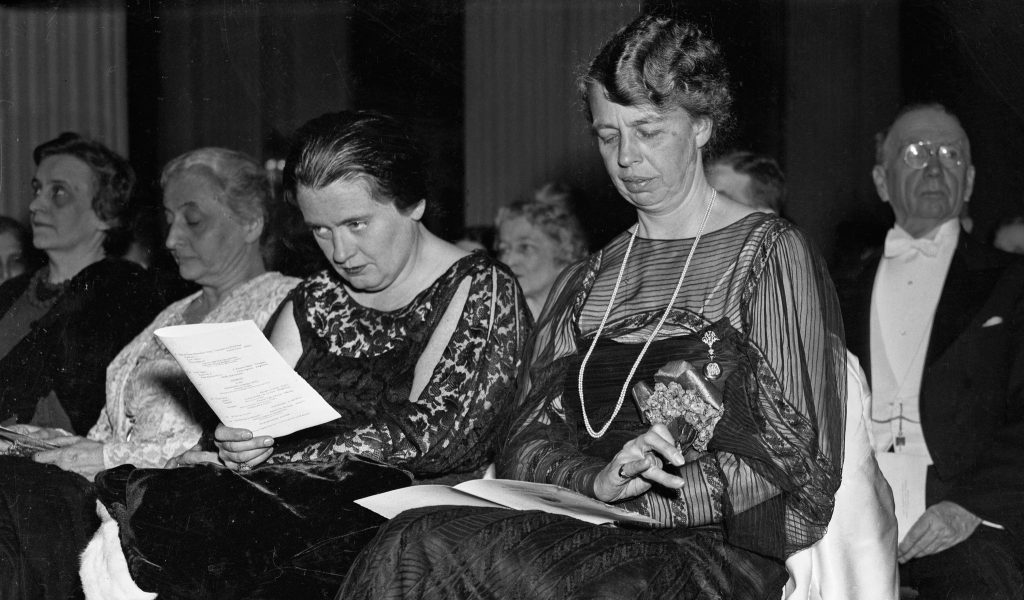

Eleanor Roosevelt endures not only as the longest-serving American First Lady, but also as one of history’s most politically impactful, a fierce champion of working women and underprivileged youth. But her personal life has been the subject of lasting controversy.

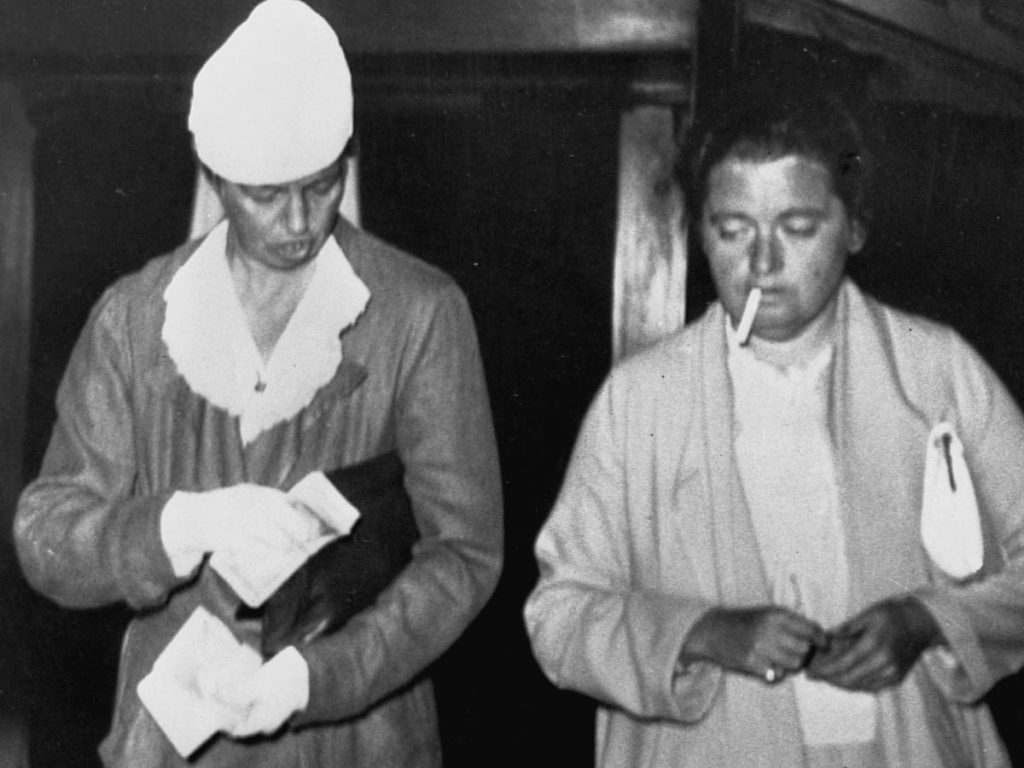

In the summer of 1928, Roosevelt met journalist Lorena Hickok, whom she would come to refer to as Hick. The thirty-year relationship that ensued has remained the subject of much speculation, from the evening of FDR’s inauguration, when the First Lady was seen wearing a sapphire ring Hickok had given her, to the opening up of her private correspondence archives in 1998. Though many of the most explicit letters had been burned, the 300 published in Empty Without You: The Intimate Letters Of Eleanor Roosevelt And Lorena Hickok (public library) — at once less unequivocal than history’s most revealing woman-to-woman love letters and more suggestive than those of great female platonic friendships — strongly indicate the relationship between Roosevelt and Hickok had been one of great romantic intensity.

On March 5, 1933, the first evening of FDR’s inauguration, Roosevelt wrote Hick:

“Hick my dearest–I cannot go to bed tonight without a word to you. I felt a little as though a part of me was leaving tonight. You have grown so much to be a part of my life that it is empty without you.”

Then, the following day:

“Hick, darling. Ah, how good it was to hear your voice. It was so inadequate to try and tell you what it meant. Funny was that I couldn’t say je t’aime and je t’adore as I longed to do, but always remember that I am saying it, that I go to sleep thinking of you.”

And the night after:

“Hick darling, all day I’ve thought of you & another birthday I will be with you, & yet tonite you sounded so far away & formal. Oh! I want to put my arms around you, I ache to hold you close. Your ring is a great comfort. I look at it & think “she does love me, or I wouldn’t be wearing it!”

And in yet another letter:

“I wish I could lie down beside you tonight & take you in my arms.”

Hick herself responded with equal intensity. In a letter from December 1933, she wrote:

“I’ve been trying to bring back your face — to remember just how you look. Funny how even the dearest face will fade away in time. Most clearly I remember your eyes, with a kind of teasing smile in them, and the feeling of that soft spot just north-east of the corner of your mouth against my lips.”

Granted, human dynamics are complex and ambiguous enough even for those directly involved, making it hard to assume anything with absolute certainty from the sidelines of an epistolary relationship long after the correspondents’ deaths. But wherever on the spectrum of the platonic and romantic the letters in Empty Without You may fall, they offer a beautiful record of a tender, steadfast, deeply loving relationship between two women who meant the world to one another, even if the world never quite condoned or understood their profound connection.

Eleanor to Lorena, February 4, 1934:

“I dread the western trip & yet I’ll be glad when Ellie can be with you, tho’ I’ll dread that too just a little, but I know I’ve got to fit in gradually to your past & with your friends so there won’t be close doors between us later on & some of this we’ll do this summer perhaps. I shall feel you are terribly far away & that makes me lonely but if you are happy I can bear that & be happy too. Love is a queer thing, it hurts but it gives one so much more in return!”

The “Ellie” Eleanor refers to is Ellie Morse Dickinson, Hick’s ex. Hick met Ellie in 1918. Ellie was a couple years older and from a wealthy family. She was a Wellesley drop out, who left college to work at the Minneapolis Tribune, where she met Hick, who she gave the rather unfortunate nickname “Hickey Doodles.” They lived together for eight years in a one-bedroom apartment. In this letter, Eleanor is being remarkably chill (or at least pretending to be) about the fact that Lorena was soon taking a trip to the west coast where she would spend some time with Ellie. But she does admit she’s dreading it, too. I know she’s using “queer” here in the more archaic form—to signify strange.

Eleanor to Lorena, February 12, 1934:

“I love you dear one deeply & tenderly & it is going to be a joy to be to-gether again, just a week now. I can’t tell you how precious every minute with you seems both in retrospect & in prospect. I look at you long as I write—the photograph has an expression I love, soft & a little whimsical but then I adore every expression. Bless you darling. A world of love, E.R.”

Eleanor ended many of her letters with “a world of love.” Other sign-offs she used included: “always yours,” “devotedly,” “ever yours,” “my dear, love to you,” “a world of love to you & good night & God bless you ‘light of my life,’” “bless you & keep well & remember I love you,” “my thoughts are always with you,” and “a kiss to you.” And here she is again, writing about that photograph of Hick that serves as her grounding but not-quite-sufficient stand-in for Lorena.

“Hick darling, I believe it gets harder to let you go each time, but that is because you grow closer. It seems as though you belonged near me, but even if we lived to-gether we would have to separate sometimes & just now what you do is of such value to the country that we ought not to complain, only that doesn’t make me miss you less or feel less lonely!”

Lorena to Eleanor, December 27, 1940:

“Thanks again, you dear, for all the sweet things you think of and do. And I love you more than I love anyone else in the world except Prinz—who, by the way, discovered your present to him on the window seat in the library Sunday.”

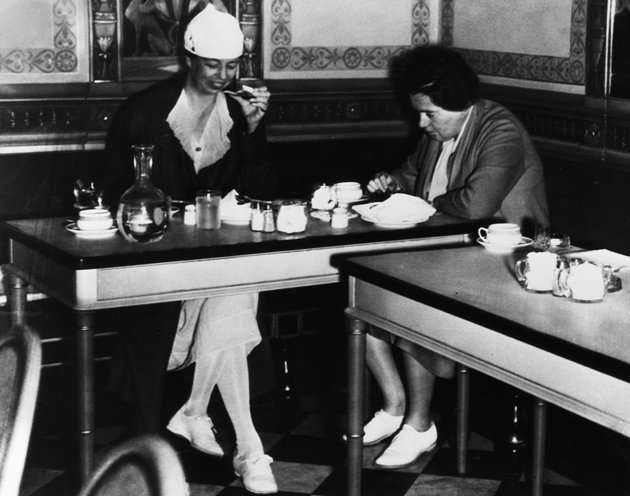

Though they continued to grow apart—especially as World War II unfolded, forcing Eleanor to spend more time on leadership and politics and less time on her personal life—Hick and Eleanor still wrote to one another and sent each other Christmas presents. Prinz, by the way, is Hick’s dog, who she loved like a child. Eleanor loved him enough to buy him a present, too.

Lorena to Eleanor, October 8, 1941:

“I meant what I said in the wire I sent you today—I grow prouder of you each year. I know no other woman who could learn to do so many things after 50 and to do them so well as you, Love. You are so better than you realize, my dear. A happy birthday, dear, and you are still the person I love more than anyone else in the world.”

If Hick and Eleanor were indeed broken up at this point, they sure are fulfilling the stereotype of lesbians hanging onto their exes. In 1942, Hick started seeing Marion Harron, a U.S. Tax Court judge ten years younger than her. Their letters continued, but much of the romance was gone and they really did start to sound like old friends.

Eleanor to Lorena, August 9, 1955:

“Hick dearest, Of course you will forget the sad times at the end & eventually think only of the pleasant memories. Life is like that, with ends that have to be forgotten.”

Hick ended her relationship with Marion a few months after FDR died, but her relationship with Eleanor did not return to what it was. Hick’s ongoing health problems got worse, and she struggled financially as well. By the time of this letter, Hick was merely living on the money and clothing Eleanor sent to her. Eleanor eventually moved Hick into her cottage in Val-Kill. While there are other letters they exchanged leading up to Eleanor’s death in 1962, this feels like the right excerpt to end on. Even in the face of dark times for them both, Eleanor remained bright and hopeful in the way she wrote about their lives together. Never one to want to share her beloved Eleanor with the American public and press, Hick opted not to attend the former First Lady’s funeral. She said goodbye to their world of love privately.